At Last, The Amazing Truth: How Average Runners Train For Marathons

We have long known how elite marathoners train, because they are fast and famous. Everyone from journalists to exercise physiologists clamors to write about their training. They run 100+ miles per week, mostly slow, but occasionally at race pace or slightly faster.

In contrast, we know next to nothing about the training of midpack marathon runners who finish in 3 hours, 4 hours, or 5 hours. They aren’t famous, and no one bothers to write about them.

Fortunately, the accumulation of GPS watch data is changing this picture. If you can’t write about one very famous marathoner, you can attract attention by covering hundreds of thousands of not-so-fast runners.

That’s what the big-data team from the University of Dublin has been doing for a number of years. Now, they’ve completed their most complete and informative paper on marathon training of midpack runners.

The paper analyzes the training of more than 150,000 marathon runners who uploaded 16 weeks of their pre-race training to Strava. The researchers then correlated the training data to the runners actual finish times.

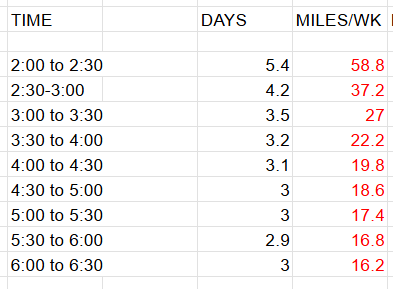

In other words, they show that if you train X miles a week, you’ll likely finish your marathon in Y:yy hours and minutes. Some of the findings will amaze you.

For example, runners finishing between 4:00 and 4:30 averaged about 20 miles/week in training. They had an average age of 40.

This isn’t the same as suggesting you only need to train 20 miles a week to break 4:30. But it does show that it’s possible, because 27,000 runners did it.

I’ve put some of the other weekly mileages and finish times in a Table at the bottom of this newsletter. We’ll hope to learn more soon when the complete paper is published. More at University of Hertfordshire.

Probiotics Boost Endurance & Lower Inflammation In Runners

I have mixed feelings about probiotics. They are promoted everywhere as a fix to just about everything. That doesn’t inspire confidence.

Also, you know the old saying: If something is too good to be true, it probably isn’t true. .

On the other hand, I have no doubt that gut health is a vast, little understood, and significant contributor to system health. And perhaps particularly to brain health. I’ve been down that path personally, after a debilitating gut-brain illness a decade ago.

So I follow the topic closely. Here’s a new probiotics paper that caught my attention because it’s a systematic review that focused on inflammation and fatigue in athletes. These are concerns to all of us.

The researchers located 13 studies with 513 participants (351 male). All studies employed a double- or triple-blinded placebo-controlled design. Subjects used the probiotics from 12 to 90 days.

Result: Ten of the 13 studies reported “ improvements in various parameters, such as, enhanced endurance performance, improved anxiety and stress levels, decreased GI symptoms, and reduced upper respiratory tract infections.”

In addition, several of the studies demonstrated that “probiotic supplementation led to amelioration [lowering] in lactate, creatine kinase (CK), and ammonia concentrations, suggesting beneficial effects on mitigating exercise-induced muscular stress and damage.”

Conclusion: “Probiotic supplementation, specifically at a minimum dosage of 15 billion CFUs daily for a duration of at least 28 days, may contribute to the reduction of perceived or actual fatigue. The authors claimed no funding or other conflict of interest. More at J of the International Society of Sports Nutrition with free full text.

Surprise! When Negative Splits Are NOT The Best Strategy

Pretty much everyone accepts that negative-splits running, or even pace, is the smart way to run a marathon. In fact, it appears that negative splits are best for any distance down to 800 meters. There’s significant data to support this.

However, some experts in computational fluid dynamics” (ie, wind resistance, and its effects on pace) have now proposed that there’s a time for positive splits. Oh, yeah? Please explain.

Positive splits are best when you are being paced by someone who won’t be able to go the whole distance with you. This would be the case when a male runner is attempting a new world-record marathon pace, for example.

By definition, no single pacer will be able to stay in front of this runner for the full 26.2 miles. The pacer might last 18 miles or maybe even 22, but not the full distance. (The official rules governing marathon races do not allow multiple pacers, which was the strategy used in Eliud Kipchoge’s 1:59:40 exhibition marathon in 2019.)

It would also be the case if you are having a friend pace you in a marathon, but that friend can’t go the whole distance with you.

Result: In this situation, the benefit of having a pacer in front of you for as long as possible outweighs the negative of starting slightly too fast. Such a strategy can improve finish times by 2.4% to 2.6% over unpaced running.

Also, there’s an ideal formation for following just one pacer. You should position yourself 4 feet behind your pacer for optimal drafting.

Conclusion: “Coaches and elite marathon runners need to be aware of this discovery, which may lead to reduced race times.” More at the prepress site Arxiv including free full text.

When You NEED New Running Shoes

We get injured for various, seemingly inscrutable reasons. Often, it’s because we make training mistakes.

We do too much, too soon, too fast. At least that’s what the injury experts and physical therapists tell us. And they are on the front lines.

However, sometimes our equipment can be an injury contributor--our shoes. A change of shoes can lead to injury, as can wearing shoes past their “expiration date.”

In my lifetime, this shoe expiration date seems to have grown shorter and shorter. We used to quote “500 miles” as a reasonable lifetime for a pair of shoes. Now I see this number gravitating down towards 300 miles.

It’s expensive and time-consuming to shop for new shoes. On the other hand, anything that keeps you running injury-free is worth the time and expense.

Several recent articles have covered the topic of shoes and injuries. Here are a couple of general shoe-injury “rules:” 1) If you ain’t broke, don’t make a dramatic shoe change; 2) If you are broke, a change of shoes alone might end a developing problem.

Visit a retail running store, and try on a number of different shoes until you find ones that feel comfortable. They should gently guide your feet through a smooth stride pattern.

Also, 3): There’s research to support running in several different pairs of shoes each week. This strengthens different muscle groups in your feet and legs.

It prevents overuse of the same muscles by the same pair of shoes. But do this carefully, a little at a time, mainly on easy days, as you let your body grow accustomed to the several pairs of shoes.

Remember that we know very little about the new super shoes with thick foams and carbon or other embedded “plates.” We don’t know how long they will last before needing to be replaced, and we don’t know if they increase or decrease injury risks.

Some runners believe in wearing super shoes on almost all their hard days--fast and long. Others believe in a much more modest use of super shoes in training.

At The Conversation, several academic and shoe-industry experts write: “Overall, we believe the most practical advice is to keep your racing shoes ‘fresh’ (under 240km, or about 150 miles), alternate a couple of other pairs during regular training, and replace them when you detect a notable drop in comfort.”

Marathon Handbook lists 11 common injuries that could be caused by worn-out running shoes. These may occur because old shoes lose much of their cushioning, and also their ability to limit excess foot movement, if this is a problem for you.

There’s no doubt that your weight makes a difference. Heavier runners will crush their shoes sooner than light-weight runners. Run Repeat even includes a mathematical formula that uses your weight to determine your shoes’ life expectancy. The formula: 75,000/your weight in pounds.

If you weigh 150 pounds, this formula yields the familiar 500 miles per pair of shoes. I’m tempted to pick a more conservative number. Because, why not choose to give yourself some room for error in the injury game?

Change the 75,000 to 60,000, and you still get 400 miles of solid, healthy performance from your shoes. More at Run Repeat.

Ultra Running Is Booming … And Raising Many Questions

Ultra-endurance events make up a small percent of all events and all participants, but often capture a lot of media attention. This is similar to coverage of other extreme adventures: climbing Mount Everest, swimming the English Channel, the Tour de France.

Research scientists are also attracted to ultra endurance. They (and we) assume there’s something extra to be learned about human health and physiology when analyzing the extremes.

Anyway, here’s a quick roundup of a few recent ultra endurance articles. Alex Hutchinson wonders what it takes to be successful in those Backyard Ultras--a great physiology, or a great brain?

It turns out that heart rate and lactate accumulation don’t seem to be limiting factors. Even the effects of sleep deprivation on the brain were less than expected.

The biggest factor appears to be “effort,” which Hutchinson admits is a “somewhat nebulous concept.” He likes to think of effort as “the struggle to continue against a mounting desire to stop.” More at Run Outside.

Two experts in the ultra-research world, Nick Tiller and Guillaume Millet, argue that “muscle damage and associated fatigue is the main impediment to performance in ultramarathons.” This damage is “more limiting than aerobic capacity, running economy, or gastrointestinal distress.” More at Sports Medicine.

A survey of competitive ultra runners vs midpack, sub-ultra runners found “that aspects of motivation, grit, and self-efficacy, but not personality, may differentiate competitive from recreational runners, and ultrarunners from sub-ultrarunners.” More at Psychology of Sport & Exercise with free full text.

An online survey revealed that “depressive symptoms appear to be highly prevalent among ultra-runners.” Depression affected 21.9% of respondents, especially females. Older runners and those not suffering from injury had significantly lower rates. Also, in a surprise finding, those running higher mileage in training did not report higher depression rates. More at International J of the Care of the Injured with free full text.

Lastly, a new report from a “large longitudinal study of ultra marathon runners” reached a perhaps-unexpected Covid finding. The ongoing project is called ULTRA--what else?--after the “Ultrarunners Longitudinal TRAcking” study. It concluded that “severe COVID-19 infection has been rare in this population of ultramarathon runners.” Only 6.8 percent of ultra runners reported “long Covid lasting more than 12 weeks.” More at Clinical J of Sport Medicine.

Cryotherapy Limits Muscle Damage, Enhances Training

Runners and other endurance athletes have been engaging in post-exercise cold therapy (like ice baths) for decades. Its use has been controversial, but many believe it enhances their recovery from hard efforts.

How about pre-exercise uses of cold therapy? That’s promising, too, and the subject of a new paper.

The subjects, all women, did two 60-minute downhill runs on a laboratory treadmill. This kind of running is known to produce significant muscle damage due to the eccentric nature of downhill running.

The two groups of women had a 4-week recovery period between the downhill treadmill runs. During that time, one group received 20 sessions of whole body cryotherapy (3 mins/session) in a small room chilled to minus 120 degrees Centigrade.

They wore lightweight running clothes in the chamber, and walked in a circle. Fourteen women did all the cryotherapy sessions, while 13 control subjects did none.

Subjects provided blood samples after both their downhill treadmill runs. The samples were analyzed for markers of muscle damage such as myoglobin and creatine kinase.

Result: Subjects who had received the 4 weeks of cryotherapy presented “a notable reduction in post-exercise myoglobin and CK levels after the second running session.”

Conclusion: “The results suggest that whole body cryotherapy can have protective effects against muscle damage resulting from eccentric exercise.” Less muscle damage could permit more and harder training.

I imagine we’ll be seeing more studies of whole body cryotherapy, and perhaps localized ice therapy, as potential enhancers of endurance training. Note: This paper did not have a performance aspect--just the blood measures of muscle damage. More at Frontiers in Physiology with free full text.

Marathon Training Of Average Midpack Runners (Continued)

Here’s a small Table showing the relationships between weekly training mileage (in red), days of running per week, and final marathon finish times of more than 150,000 marathon runners of all ability levels. The analysis comes from big-data experts at the University of Dublin who had access to Strava data from 2014 to 2017.

When considering all 150,000+ runners, they had an average age of 39.5 years, an average finish time of 3:50, and an average training mileage of 28 miles/week. They ran 3.6 days/week, and completed an average long run of 12 miles.

SHORT STUFF You Don’t Want To Miss

GREAT QUOTES Make Great Training Partners

“We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

--Oscar Wilde